“Letter Perfect

Letterpress artists revitalize the almost-obsolete process at Pyramid Atlantic. Also: Work by Cheryl Ann Bearss, Pam Frederick, Harriet Lesser, Veronica Szalus, Dee Levinson, and Monica Jahan Bose

MARK JENKINS

JULY 2ND, 2025

David Wolske, “Polysynthesis” (Pyramid Atlantic)

"FREEDOM OF THE PRESS is guaranteed only to those who own one," wrote A.J. Liebling in 1960, before not just the Internet but also the widespread adoption of offset printing. Liebling's words would originally have been promulgated by letterpress, a once-dominant industrial process that now survives as the artisanal craft showcased in Pyramid Atlantic's "Press On." Fittingly, this large and impressive exhibition includes Khoa Nguyen's elegant poster of Liebling's maxim, the sentence neatly choreographed in highly compressed orange sans serif text.

Letters and words are central to the show, which was juried by Celene Aubry of Tennessee's Hatch Show Print and Allison Tipton, manager of the Globe Collection and Press at the Maryland Institute College of Art. There are images in many of the works made by the nearly 100 contributors (some working as members of teams), and a few contain not a single letter. But several of the most inventive pieces demonstrate how just color, layout, and type are sufficient to build an effective composition.

Words and names, especially when they're well-known, can be read even in daringly unexpected configurations. So Scott Fisk tightly overlaps the letters in "home" and "joy," emphasizing color but not entirely forgoing legibility. And Virginia Green flips sideways and breaks into two lines the longest name in this familiar lineup: John, Paul, George, and Ringo. Similar tactics, with the additional complication of multiple typefaces, enliven Frank Baseman's bold poster of the NATO phonetic alphabet, all the way from "alpha" to "zulu."

More minimalist but just as astute are E Bond's sculptural arrangement of industrial-looking "E's" in corroded shades of black; Steven Stichter's punning waves of rising blue "C's"; and Richard Kegler's duo of superimposed ampersands, one upside down. David Wolske abstracts letters by trimming them merely to such features are bowls and serifs, printed in vivid hues and partly overlaid. Carlos Hernandez uses mostly letters and punctuation -- but also silhouetted guns -- to depict cowboys identified as good, bad, and ugly. Jon Drew's gentle landscapes position black trees in front of terrain built mostly of letters.

As might be expected, there are numerous artist's books and other 3D items. Cynthia Connolly's sewn grab bag contains 15 postcards, mostly of her photographs. Andre Lee Bassuet demonstrates the letterpress-worthiness of the Korean Hangeul alphabet in a tiny book printed with Legos. Richard Zeid imprints the word "fractured" atop a black-and-white photograph that's been torn into four irregular quadrants. Elinor Swanson prints blue-on-white patterns that suggest Dutch ceramics and presents them both flat and folded into the shapes of a cup and a pitcher.

Among the most powerful entries, both in theme and form, is Sarah Matthews's "Outrage," a flag book that stands like a poster and conveys the artist's response to the overturning of Roe v. Wade. "My uterus is none of your business" proclaim black-on-pink letters that stutter across repeated unfurled pages. Matthews's broadside -- and all of "Press On" -- certifies that letterpress is anything but quaint.

Cheryl Ann Bearrs, “Great Falls November” (Studio Gallery)

THE NATURAL WORLD IS THE INSPIRATION for Cheryl Ann Bearss's Studio Gallery show, as it was for her previous one. But the focus of "Fleeting Moments of Nature" has expanded from closeups of individual trees to wider views of forests, skies, and rivers -- notably the Potomac at Great Falls, a turbulent contrast to the Northern Virginia painter's serene pictures of flowering bushes and trees.

Her style has also shifted toward a more detailed and realistic approach, although some of her oils are looser than others. This can be seen even in pictures of the same essential subject. "Great Falls November" is tighter than "Stormy Skies over Great Falls," although both depict rock and water, sunlight and mist.

Bearrs hasn't abandoned renderings of single trees, including one viewed from a craned-neck perspective. All black and gray, "Snow Tree" is among the show's most elegantly stylized pictures, and such stark, leafless studies as "Twisted Trunks" have an almost-sculptural quality. Removed from their natural environs, such gnarled wooden spires have a totemic quality.

Also at Studio is "At This Time," billed as three "coordinated shows" by Pam Frederick, Harriet Lesser, and Veronica Szalus. Least like the other entries are Lesser's pictures of rumpled bedclothes, manipulated photographs that incorporate drawing and painting. Meditations on "waking up," the mixed-media pictures contrast soft and hard by mounting images of twisted fabric atop steel panels.

Both Frederick and Szalus use recycled materials. The former's installation employs found cardboard in a rhythmic composition that was inspired by a Herbie Hancock track and visually suggests Matisse, Mondrian, and Russian Constructivism. The latter's 3D assemblages appear more ominous: What appear to be toilet-paper rolls, often painted and sometimes singed, are held in place by a slice of a pipe or a ragged chicken-wire tower. Where Frederick's collage has a funky equanimity, Szalus's constructions conjure a universe that's haphazard, damaged, and dangerously unstable.

Dee Levinson, “Egyptian Woman” (Touchstone Gallery)

ANCIENT EGYPT AND ITS ENVIRONS ARE THE WELLSPRINGS of Dee Levinson's "Egypt Revisited," but the Northern Virginia artist doesn't imagine her subjects as they might have been. Instead, she models most of the oil paintings in her Touchstone Gallery show on her photographs of historical sculptures. The resulting images have a strong sense of physical presence, but they seem as much stone as flesh.

Levinson worked for more than two decades as a graphic designer for the Washington Post, and her commercial-art background is evident in her meticulous illustrative style. Unlike some artists with a similar history -- Andy Warhol, notably -- Levinson doesn't contrast hard lines with areas of looser, freer color. But she does subtly mottle the primarily single-hue backdrops, and employ boldly unnaturalistic color schemes. Earthy tans and browns are set off by vivid red, blues, and purples, and gold and copper tones evoke the riches of Pharoanic Egypt.

The artist primarily depicts historical Egyptians and their vestiges, including masks and mummies, as well as the occasional goddess (Isis) or out-of-towner (Persian emperor Darius, who ruled Egypt long after the best-known pharaohs). Ramses II is portrayed in three separate color schemes, although the hues aren't the only differences between the renderings. Each seated figure is placed inside a different painted border, the use of which is another Levinson trademark. The artist presents ancient Egyptian history as tidy and contained, ready for the viewer to unbox.

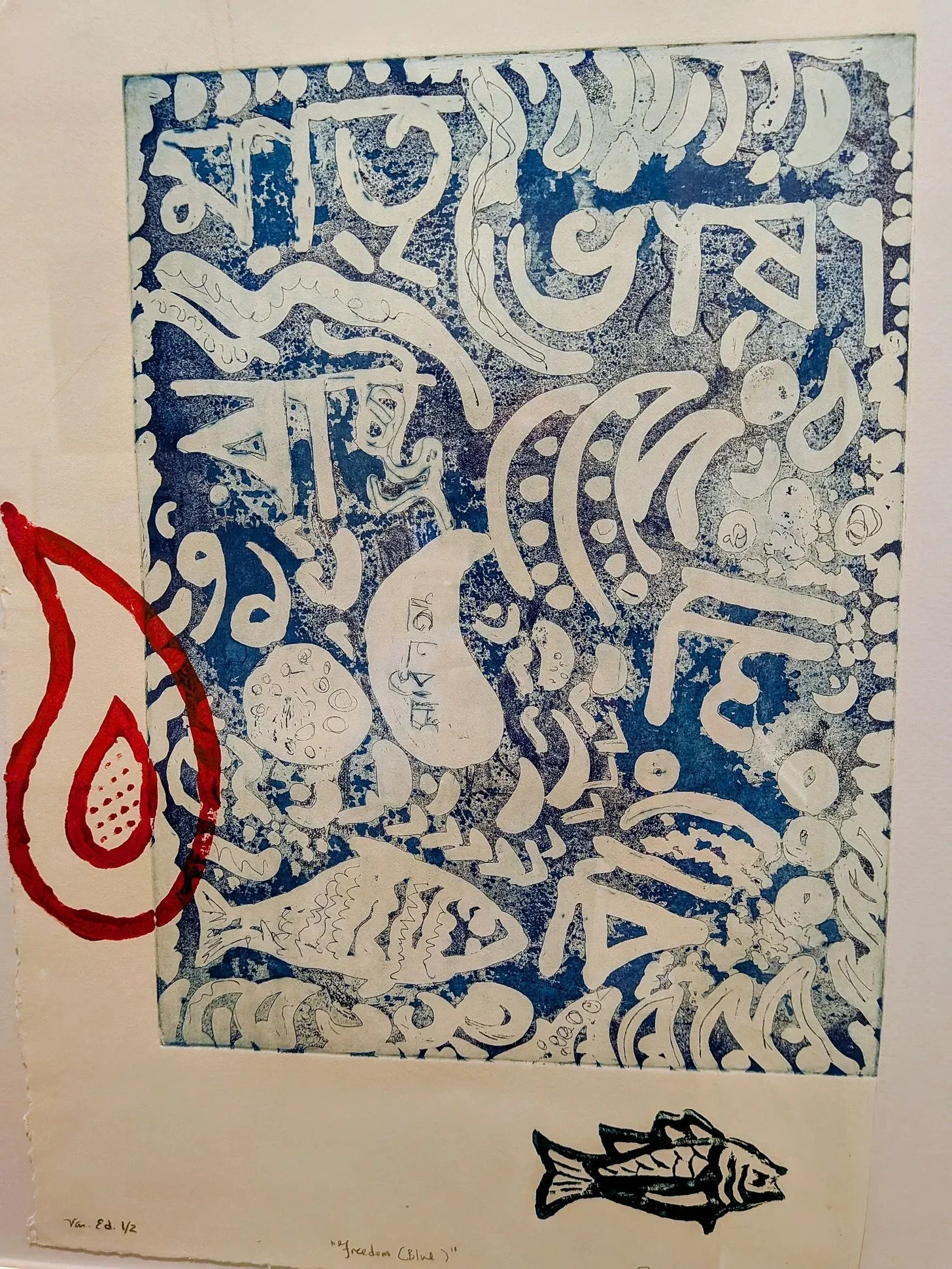

Monica Jahan Bose, “Freedom (Blue)” (photo by Mark Jenkins)

HANGING CURTAINS MADE FROM SARIS mark the entrance to Gallery Y's "Take Me to the Water," a flourish that comes as no surprise. Repurposed saris are among the customary elements in Monica Jahan Bose's work, which is often collaborative. The Bangladeshi-American local artist enlists contributions from women in her ancestral village on the Bay of Bengal -- an area especially vulnerable to rising sea levels -- but also from people who live near the notoriously polluted Anacostia River. Among the results was "Swimming," last year's public installation near another body of water, D.C.'s Marie Reed Aquatic Center.

Some pieces from "Swimming" surface in Bose's current exhibition, but this show is smaller and focused mostly on woodblock and relief prints. Some of these incorporate painting and drawing, and several include small scraps of saris. Of these, the most striking is "Rising (with Sari)," which is all green except for a slash of magenta cloth. The strip offers a strong color contrast while evoking the fluidity of both water and fabric.

Bose's eclectic art is held together by its themes, even as multiple hands and voices pull it in various directions. Phrases in English and Bengali punctuate the imagery, and one sari is bordered again and again by "1.5°C" -- the amount of global warming that's estimated to be sustainable. But the most universal emblems are simple renderings of water and fish, traditional symbols of purity and abundance that have come to represent the opposites or their longtime meanings.

Press On

Through July 13 at Pyramid Atlantic Art Center, 4318 Gallatin St., Hyattsville. pyramidatlanticartcenter.org. 301-608-9101.

Cheryl Ann Bearss: Fleeting Moments of Nature

Pam Frederick, Harriet Lesser, and Veronica Szalus: At This Time

Through July 12 at Studio Gallery, 2108 R St. NW. studiogallerydc.com. 202- 232-8734.

Dee Levinson: Egypt Revisited

Through July 6 at Touchstone Gallery, 901 New York Ave. NW. touchstonegallery.com. 202-682-4125.

Monica Jahan Bose: Take Me to the Water

Through July 11 at Gallery Y, YMCA Anthony Bowen, 1325 W St. NW. www.ymcaanthonyboweneventspacedc.com/galleryy. 202-232-6936.”

Review by Mark Jenkins, DisCerning Eye, July 2025. Thank you!